Eighty-five thousand years ago, the spectacular twin Los Chocoyos volcanos erupted in a major seismic event which spread ash from Guatemala as far south as Panama and formed the volcanic crater that today holds Lago Atitlán. Renowned as one of the world’s most beautiful lakes, Lago Atitlán is twelve miles long and over a thousand feet deep, held by mountainous folds of trees, coffee and corn. Rising above this spectacular setting are the volcanos San Pedro, Santiago and Toliman. Beneath them Tz’utzujil Maya pueblos with concrete houses in yellow, pink and blue are interspersed with hives of traditional adobe and tin roofed homes, tumbling bougainvillea and bananas drooping with crowded hands of fruit. On the lake fishermen stand paddling shallow wooden boats, unfolding hand lines as they roll their wrists one over the other.

In 1995 I visited Santiago Atitlán as a member of Vashon’s sister city committee. Sixteen years later I returned to Lago Atitlán and revisited Santiago and neighboring San Pedro La Laguna. I was afraid the traditional Maya way of life had been ruined by modern commercialism and inclusion on the gringo trail. San Pedro has indeed changed hugely since the day I required a guide to lead me down the narrow paths through coffee and corn to find a hidden hotel . But in this 96% Tzu’tujil pueblos, Maya identity and tradition continues to live, even as the town has graciously grown to meet the needs of budget visitors from around the world who come to learn Spanish, to live in a Maya homestay, to volunteer, or like me, in search of a more connected and vital daily life.

As a writer with a PhD in Creativity and Communication, I am passionate about “live” experiences

In San Pedro as thoughout Guatemala, most Maya women wear traje, traditional handwoven clothing: a huipil which is distinctive to each pueblo, a faja, a wide intricately decorated belt which secures the corte, a multihued woven skirt. The traje of the women maintains and affirms Maya cultural identity -- the patterns, colors and figures on the cloth tell a story of Maya cosmology and history. Their cloth is made to be washed on rocks. It survives to be passed down through generations while also supporting local craftswomen.

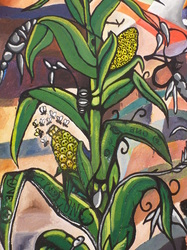

In the morning women carry heavy plastic baskets of laundry atop their heads and possibly a baby in a rebozo firm against their backs, following narrow paths to wash on the ancient flat rocks in the lake. In the space between homes and restaurants corn sways with the wind and squash plants offer up goldenrod blossoms, while pink frijole pods and red coffee cherries dry on roofs and cement pads. Men in sombreros with machetes at their sides carry loads steadied by worn trumplines across their foreheads, their bags heavy with wood, corn and coffee from the campo.

And yet, there is always time for us to exchange greetings, “Buenos dias,” my neighbors and I call to each other as I wander down the street for my fresh orange juice. Que te vaya bien”, have a good journey, they may add. The words are sung, not rushed, and given eye contact and a smile. Of course this can only happen if people are walking or sitting along the street. There is no need for a car here—and most people cannot afford one -- so everything is within walking distance or accessible by public transportation. Life on the street is still a form of entertainment.

It is true that no visit to Guatemala is complete without the ancient Maya ruins, the charming colonial city of Antigua or the unsurpassable Lago Atitán. I have lived in all of these areas since coming to Guatemala over two years ago.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed